With over 25% of the world’s children experiencing failure to thrive (FTT), stunted growth, and or delayed development, it is a good time to look at the various facets of pediatric nutrition that require particular attention (1). Recent assessments of pediatric malnutrition have indicated that the influence of one or more micronutrient deficiencies on the trajectory of a child’s health may be far greater than previously thought and that clinicians must consider a much larger number of nutritional factors than energy and protein intake (2). An over reliance on assessing nourishment by the use of typical anthropometric values, can provide a false sense of adequacy. While the classic model of FTT relies upon the use of height and weight growth charts and percentiles, there may be neurological or other developmental delays that are equally tied to malnutrition.

While there are still a majority of FTT cases that are a function of inadequate intake, more research indicates that a significant percentage of children suffer from FTT secondary to enteric infections (2,3). Many of these infections and pathological cases of dysbiosis create intestinal environments and/or microbiome ecosystems that prevent normal micronutrient absorption. Some infections damage the mucosal layer of the gastrointestinal tract. Others may create deficiencies by altering normal transit times, often through diarrhea or loose, watery stools that greatly reduce normal mucosal layer-nutrient interface, required for absorption. These gut-based infections are gaining greater appreciation as a primary cause of FTT and delayed development throughout the world, including the United States and other highly industrialized countries. Malnutrition is often seen as a disease that only affects children in developing areas of the world, where food is scarce. However, both malnutrition and FTT are prevalent among other areas and populations around the world.

It is important to look for both anthropometric and biological signs of nutrient deficiency. Utilizing height and weight charts, growth records, as well as examining children’s typical nutrition-related biomarkers such as hemoglobin (Hb), ferritin, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), total iron binding capacity (TIBC), serum zinc, and vitamin D levels (25(OH)D3). Digestive issues and/or malabsorption need to be considered or evaluated if there is evidence of FTT or micronutrient deficiencies despite what appear to be adequate dietary intake.

The primary causes of enteric infection or environmental enteropathy can be screened for with diagnostic approaches that range from breath tests for particular pathogens of bacterial overgrowth patterns to stool analyses. Tests that can detect microbes, fungi, or protozoans known to disrupt normal gastrointestinal function or nutrient metabolism should be used with evidence of diarrhea or accelerated GI transit.

Food patterns are intricately linked to both dysbiosis and other causes of intestinal wall pathology. While sugars and refined carbohydrates may foster the growth of pathogenic bacteria and exacerbate gut infections, specific foods such as those rich in gliadin, soy protein, or casein may also interfere with normal GI function. These food intolerances should be fully explored as major components to the child’s health challenges. Research suggests that children are highly susceptible to both FTT and micronutrient deficiencies with exposure to foods that are poorly tolerated (4). Luckily however, research also supports the effectiveness in helping restore health when these foods are eliminated. Eliminating gliadin or following a gluten-free diet serves as the best example of this (5).

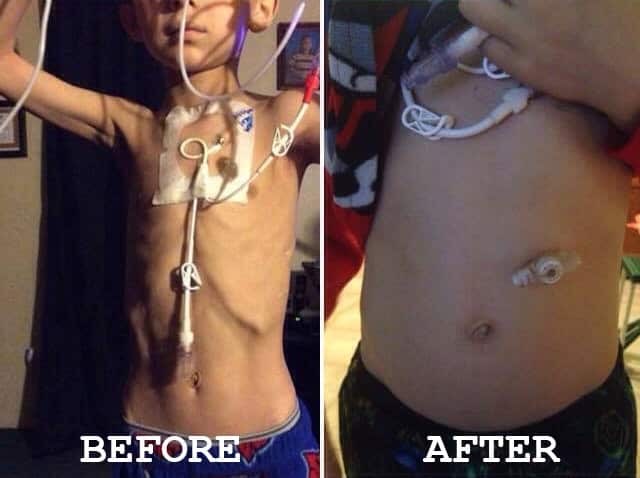

In summary, it is important to consider both a wide variety of nutrients and potential causes of FTT. While malnutrition is the cause of most cases, the mechanism ultimately responsible may be an enteric or gut-based infection or dietary exposure to non-compatible proteins. Assessment should potentially include microbial testing, food records, blood biomarkers associated with micronutrient and/or absorption levels, as well as classic anthropometric measurements. If there is evidence of bacterial overgrowth, the appropriate treatment may require both antibiotics and probiotics for long term success and remission. With food intolerance(s) suspected, an elimination or modified elimination diet should be considered. The use of enteral nutrition is often considered with younger children demonstrating FTT. In this case it would be wise to choose an enteral formula that contains no gluten, soy, corn, dairy, eggs, or chemical additives and that is particularly low in fructose. This type of enteral formula will avoid the most common ingredients that cause absorption issues while also reducing any contributions that could be made to an infection.

~ John Bagnulo MPH, PhD.

RESOURCES:

1. Owino V et al. Environmental Enteric Dysfunction and Growth Failure/Stunting in Global Child Health. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20160641. Epub 2016 Nov 4.

2. Bouma S. Diagnosing Pediatric Malnutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017 Feb;32(1):52-67. doi: 10.1177/0884533616671861. Epub 2016 Oct 23.

3. DeBoer MD, Lima AAM, Oría RB, et al. Early childhood growth failure and the developmental origins of adult disease: Do enteric infections and malnutrition increase risk for the metabolic syndrome? Nutrition reviews. 2012;70(11):642-653. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00543.x.

4. Nurminen S, Kivelä L, Taavela J, et al. Factors associated with growth disturbance at celiac disease diagnosis in children: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterology. 2015;15:125. doi:10.1186/s12876-015-0357-4.

5. Sansotta N et al. Celiac Disease Symptom Resolution: Effectiveness of the Gluten-free Diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Jan;66(1):48-52.